BLOG ARTICLE

The hidden cost of wild-caught invertebrates

It’s often tempting to buy the biggest and most impressive specimens, but if those animals have been taken straight from the wild, there are issues you should be aware of.

The hidden cost of wild-caught invertebrates:

Why you should buy captive-bred

You’re excited to own your first pet spider. You’ve ordered online and now the day you’ve been waiting for has come. Your package arrives. Gently, you peel back the layers and lift out the spider inside. It’s beautiful! You take a photo to show it off online. You look forward to many happy years together. A week later, it dies. You start to wonder: where did your pet come from?

In May 2022, a paper looking at the global arachnid trade was published, highlighting the dangers and unknowns of the growing popularity of pet spiders. It was noted that, at least on a global scale, the majority of animals being sent back and forth, and the majority of species being traded, were coming directly from the wild. The impact this is having on the conservation of these species is nearly impossible to measure, so there is no way to determine which species could be experiencing a serious threat to their survival.

Australia is an unusual case. Our wildlife is protected, which means it cannot be easily poached and exported into the worldwide pet trade (though many popular species have been smuggled out). However, within Australia, there are few regulations on the collecting and sale of invertebrates, and those that exist are not easily enforced. This leaves our native invertebrates in a sticky situation.

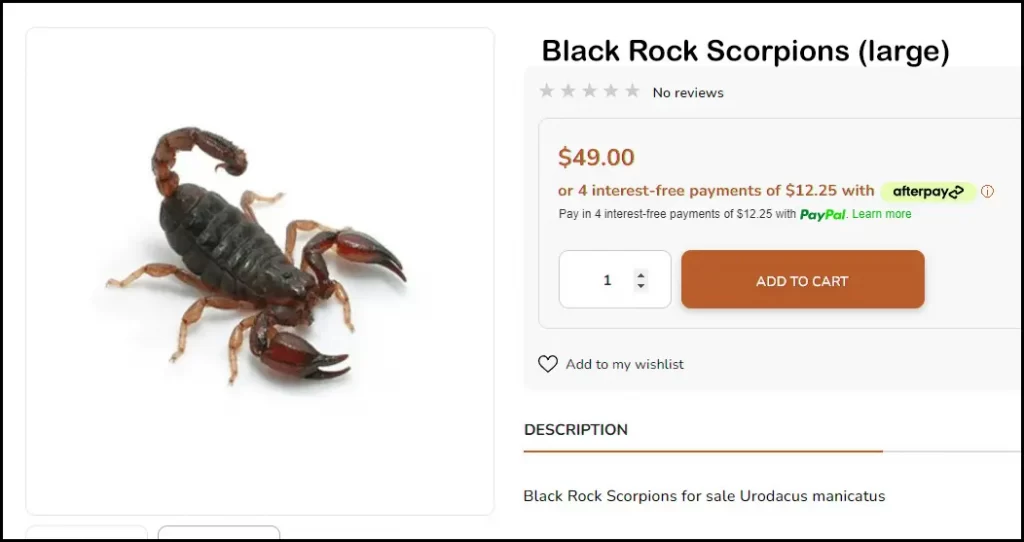

Overcollection for the pet trade is a potentially very serious threat to the conservation of our invertebrate species. Once a species becomes popular, demand outstrips existing supply and opportunistic collectors head out into the wild to catch individuals for sale. For some especially coveted species, this could translate into hundreds of dollars for a single animal, so collectors are incentivised to harvest large numbers of wild individuals and sell them directly to customers.

For long-lived and slow-breeding invertebrates such as tarantulas, scorpions and Giant Burrowing Cockroaches, the problem is particularly apparent. Taking years to rear a juvenile to adulthood, pet owners would understandably prefer to buy an animal that is already large and impressive. The easiest and fastest way to obtain an adult for a seller is to poach them from the wild. Some of these animals may be upwards of twenty years old when they are collected and sold. Collecting from the wild may look like a win-win for the people involved, but not only does it put the survival of the species in danger, it also has hidden costs for the new pet owner.

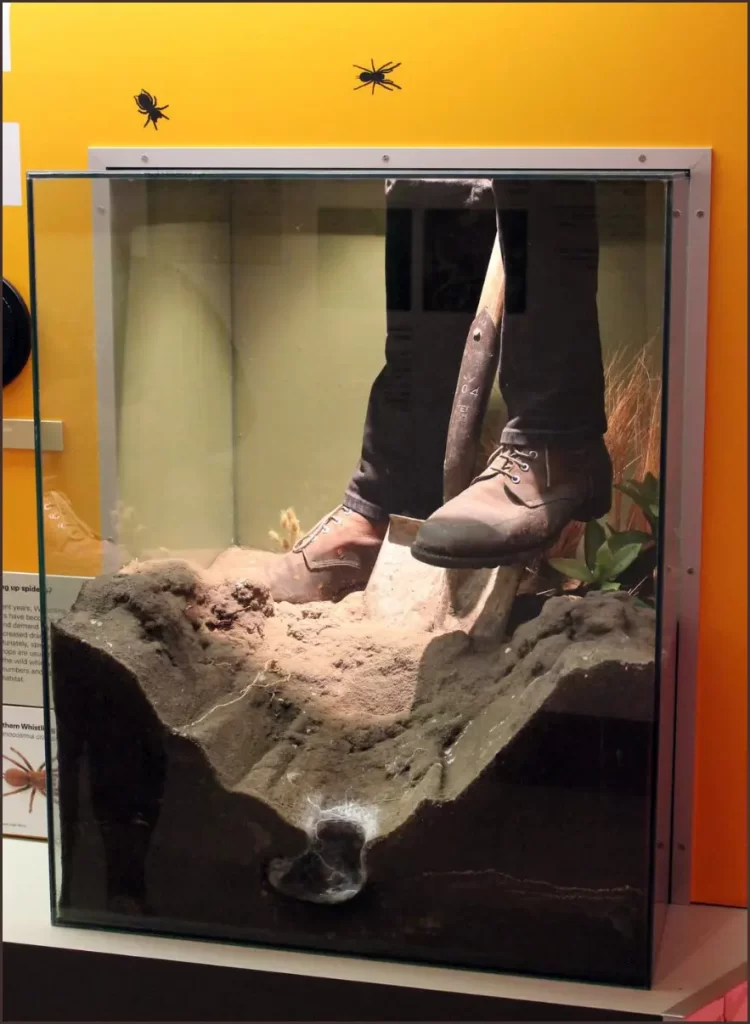

To understand the conservation threat posed by wild harvest of invertebrates in the pet trade, you need only to imagine this scenario: a particular slow-breeding scorpion from a particular small area becomes popular. A collector goes out to catch, perhaps, twenty adults for sale. The collector doesn’t know how big the population is, but guesses this is probably not going to harm the species. Meanwhile, another collector comes to the same area. They collect thirty. Again, they guess that thirty isn’t a large number and probably won’t hurt the population. After this, a third collector picks up ten more. That’s sixty adult scorpions now missing from this population in a short period of time. Is the local population a thousand adults? Is it a hundred? Without good information on species and their populations, we have no way of assessing the damage this kind of commercial activity can do.

Wild harvest of invertebrates may threaten the survival of the species and financially rewards unsustainable collectors. In this process, huge amounts of damage can also be done to the habitat through activities such as mass digging or rock-flipping, where poachers make no effort to restore the environment to its original state. There’s also an additional consideration for the new owner of this pet: the health of the animal.

Surviving in the wild is a serious challenge! The invertebrates you purchase that come directly from the wild are of unknown age and might be nearing the end of their lifespan. They are frequently carrying mites and other parasites, some of which can be fatal but may not be discovered until after you’ve made your purchase. Additionally, sellers who collect and sell from the wild may not be able to replace any animals they have sold in poor health, because they simply don’t have any more. This leaves owners potentially out of pocket and with nothing to show for it, often unfairly blaming themselves for the animal’s death.

One more hidden problem with buying a wild-caught animal, especially when it comes to species that are new to the invertebrate-keeping hobby, is that the collector may have never had to care for it. If the animal has been collected from the wild and then immediately on-sold, there may be no information available on how to properly care for the animal and what it needs to survive – resulting in its premature death.

Fortunately, there’s a way to avoid all these scenarios, and that’s to only buy animals from captive breeders. These breeders, which include Minibeast Wildlife, only collect wild adults in very small numbers to build and maintain a sustainable breeding population. Juveniles from these adults and future generations form the basis of a sustainable, healthy source of invertebrate pets that effectively address the threat to their wild cousins, and ensure that pet owners receive a young, healthy animal free of parasites and with tried and tested care information. Captive breeders are also able to provide better support to you because they have potentially spent years caring for those same animals.

Working out which sellers are wild harvesting can be tricky, because usually they don’t want you to know! To find an ethical captive breeder, you want to look for sellers who sell juveniles rather than adults, and who don’t have large numbers of species listed with only a few of each available – this indicates wild collection activities. You also want to make sure that these breeders have a policy for replacing minibeasts that arrive in poor health and that they can support you if things go wrong. All these are good signs of a knowledgeable captive-breeder at work.

Remember that captive breeding is no mean feat. It requires a huge amount of knowledge about the animals and their care. It requires breeding space and potentially years of work before animals are available to purchase. For this reason, captive-bred invertebrates are usually more expensive and it can be tempting to look for cheaper and less sustainable options. In the end, it’s up to our community of invertebrate keepers to look after Australian biodiversity by making informed choices that protect our future, and encourage the practices we want to see.

Check out our spider collection

Article written by

- Caitlin Henderson

- August 2022

Do you like this article? Share it on your favourite platform.

You might also be interested in

How to tell the sex of Australian tarantulas

Is your tarantula a male or female? How can you tell? In this article we’ll show you how to sex your tarantula!

How dangerous are spiders?

The truth about Australia’s most deadly bugs that bite and sting

Minibeast Wildlife’s bugs visit schools in Cairns

Minibeast Wildlife is engaging students throughout the Wet Tropics, visiting schools in Cairns, the Northern Beaches and the Tablelands.

The Hidden Cost of Wild Caught Invertebrates

It’s often tempting to buy the biggest most impressive specimens, but if those animals have been taken straight from the wild, there are issues you should be aware of.